Rejection is a powerful force. It can help us defy the status quo and can become a never-ending well of motivation. But it can make us waste years of time and energy. Most of the successful people I know have strong rejections: of authority, monopolies, a way to do certain things, etc. They are the freethinkers that sometimes change a part of our society. But at the other side of the spectrum, most of the unhappy people I know embody dozens of rejections: fear, family grudge, lack of love, … They didn’t build on rejections, they were defined by their rejections.

Build on the right rejections, and avoid being weighed down by the bad ones.

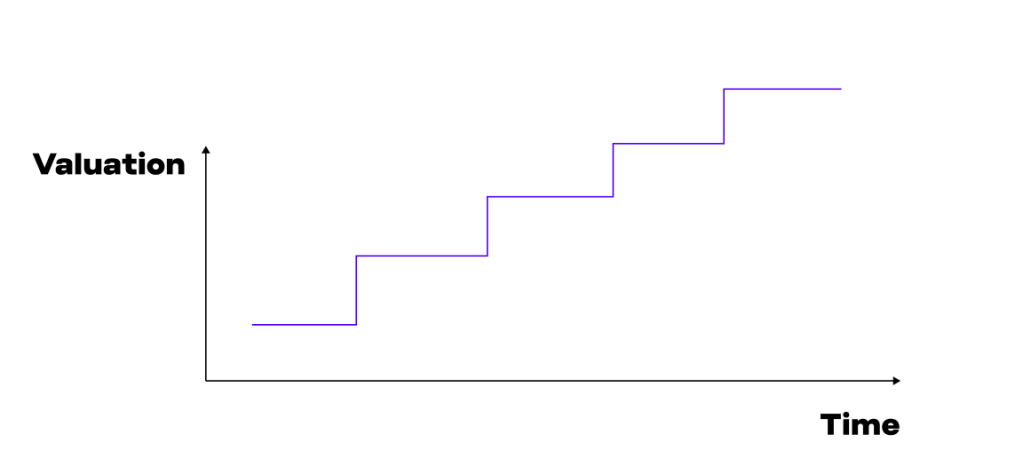

Mark’s story

Mark is a genius developer at UnicornTech. He’s 30, nice, loves people, and is great at what he does: coding. UnicornTech’s CTO sees the potential in Mark and promotes him to VP Engineering. Mark takes the job despite his impostor syndrome and starts to manage 20 developers.

At first, things go well. Then a few people-issues arise and HRs aren’t of any help to Mark. Mark solves a few cases and has to fire one developer. It’s tough for Mark but it goes over it. A few months later, Mark’s team is in trouble: projects go over deadlines, a few members quit and others complain about the lack of recognition from UnicornTech. Mark compensates himself for the departures and tries to manage the complaints as best as he can.

18 months after his promotion Mark is burned out and way more cynical: “People always complain, they never take ownership and I can’t stand to babysit everyone anymore”.

So Mark quits.

“I’m a great developer and originally that’s what I loved. I accepted the VP Engineering position because my friends were happy about the opportunity, but I’m not good at management. So let’s become an individual contributor again and make as much money as before, without the trouble of handling people”.

As the market is dynamic, Mark finds a new job 3 weeks after quitting UnicornTech and starts as a senior developer. 6 months in and Mark starts to disagree with his manager’s strategy. For Mark, objectives are unclear and the company focuses on the wrong things. The situation with his manager gets more tense, and 6 months later, Mark quits again.

“I can’t stand managers that make bad decisions. I want freedom. I want to work on what I want. So let’s become freelance”

As Mark has great skills, he finds a few clients quickly. But work isn’t as exciting as it was. Some projects are rushed and some never finish. Mark isn’t socially integrated with his clients’ teams, and Mark spends more time coaching his clients than writing code. Mark spent 12 more months freelance and decided to find a new job.

“I’ve accumulated a lot of experience in those past 4 years. If I want to maintain my salary and social prestige, I’ll have to find at least a Manager position”. And so does Mark.

And the story repeats itself.

See what Mark did? He systematically looked for a new job that fixed the main discomfort he previously had. Management is tough? Stop managing. Can’t do whatever you want? Ditch all social structures and become freelance.

Mark built his career on rejection.

Mark’s career started on fertile ground: he was skilled, people-loving, and young. But by building on rejection, Mark decided to cut every branch that didn’t blossom immediately. Today his career is far away from a fast-growing specialized bamboo, and not as strong and solid as a bonsaï. His career is a shrub at most.

Marks are everywhere

Mark’s story is not the only one. After hundreds of interviews for different positions, I’ve seen this pattern again and again. The most common examples are:

- My previous startup failed financially -> I want the stability of a big corp. Never mind the politics.

- As a manager, I can’t stand people anymore -> let’s become an individual contributor. And ditch the strategic vision and collaborative impact.

- The reason I failed my last venture was because we focused too much on SMBs -> my next startup will be focusing on big Enterprise clients only. Even if all my expertise lies in SMB.

People keep cutting those blooming branches and start over again.

Rejection is multi-variables

Building on rejection by itself is not bad. The problem is to not be focused enough on what we want to reject.

So when you experience the temptation of building on rejection, try first to deconstruct the rejection in several dimensions. What your environment looked like? How mature were you? Did you give your best? Was the output in your control or not? Etc.

An example of a first position in management at a startup that didn’t go well:

- Environment: what was my startup’s culture? Was it positive or toxic? Was my team nice? Was performance ok in my team before I became manager?

- Maturity: was I ready for this position? Did I want it at the start?

- Stage: was it my first time managing? What do I think I’ve mastered and what are the things I need to improve as a manager?

- Transition: was I supported during my transition to management? Was my startup providing training? Was my operational workload manageable?

- Output: did I have the possibility to hire/fire whoever I wanted? How was my team when I first started? Did some decisions external to the startup impact my management?

- Etc.

If we deconstruct Mark’s story, we may find that going from 0 to 20 people to manage in a few months, in a toxic company culture, without training and without operational workload decrease was.. a recipe for disaster, even for the best naturally-born manager. Mark wanted the job (he loved people) and was mature enough. He surely made mistakes as a first-time manager, but those are natural. By deconstructing the situation, instead of building on rejection (“management, never again“), Mark could have found another position in a positive-culture startup, asked HR for management training, and restarted with a 5-10-person team. He would have grown as a strong manager and accessed a VP position in a company he would not have dreamed of a few years before.

In medio stat virtus

La vertu se tient au milieu

Don’t underestimate “bad luck”. While luck is something we can influence, no one would dare to “reject bad luck”, right? Sometimes your startup fails because a new law is passed. It’s out of your control, and that’s it. Does it mean you’re a bad entrepreneur? No.

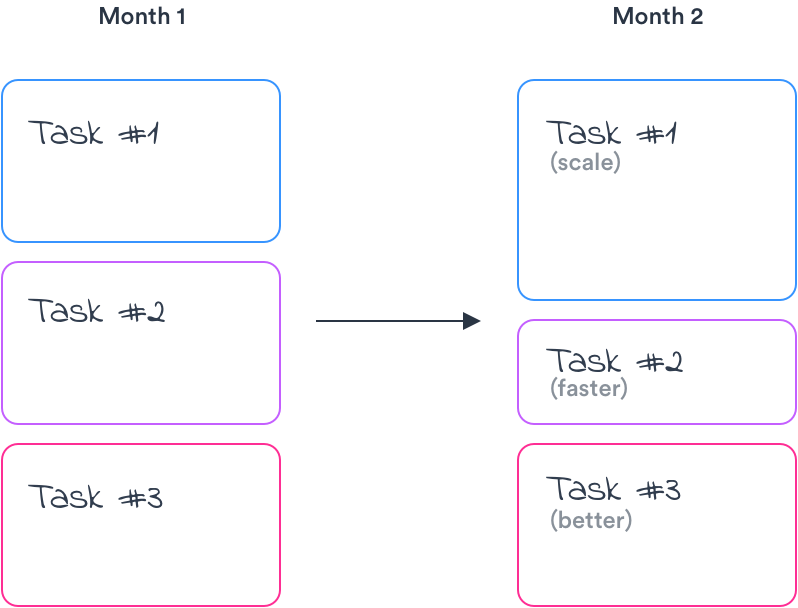

Interconnection

When we have deconstructed our global rejection and know more precisely what we want to reject in particular, it’s time to shape our ideal. But before doing that, we need to look for interconnections. Without taking into account the price of rejecting something, we will build an ideal picture that won’t apply in the real world. So we have to understand what it implies to reject something and see if we bear to pay the cost. The best question to ask ourselves is “What do I trade?”.

For example, going from a startup to a big company is usually a big trade. We trade:

- A high-risk / reward environment vs. a low-risk / reward environment: better average financial stability in big corporations, but better career growth opportunities in startups

- Agile vs. organized: more erratic “just do the thing” way of work in startups, and more predictive and rigid in big corps

- Individual impact vs scale: more individual impact in startups, and bigger projects in big corps

Some interconnections may be cliché and need to be checked: some startups are safer than big corps and some big corps are faster than startups. But structurally it’s a given that you need more process to manage 10 000 people than when you’re a team of 10 people. By understanding the organic structure of your future environment, you will be more prepared to understand what are the trades.

When the interconnections are found, the only remaining question to ask is: is it a good trade? If we lose more than we gain on one dimension, can we narrow the size of our ideal picture, so that we don’t have to trade on one dimension?

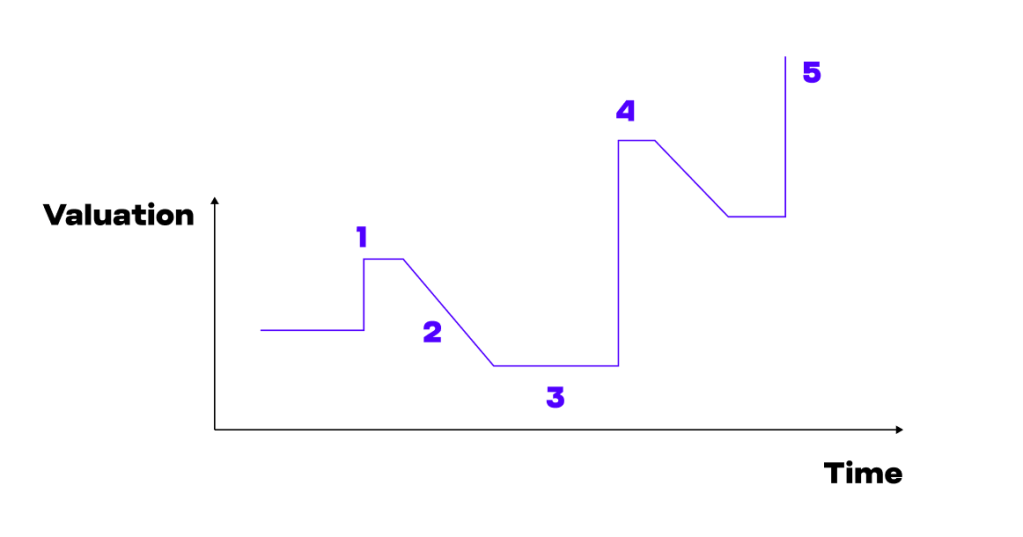

Group rejection

A lot of management decisions are built on rejections. Improving a team is like building muscles: to grow you need to break some things and rebuild them. So it’s normal to reassess what one is doing. But if bad management were a movie, it would be most likely [rejecting] everything everywhere all at once (John Cutler would argue that it would be called In the Dark). Bad managers add new stairs but destroy the building’s foundations by doing so.

Let’s Franck as an example. Franck just joined the company as VP Engineering. The CEO gave him a mission: “We’re not fast enough. Please accelerate our team’s velocity”. The message is clear: reject slowness.

What does Franck do at his first meeting? He put a new value on the wall: speed. He focuses all his team on velocity. Of course, he tells his colleagues to “keep doing the same good work, but try to make it faster”. And so people do.

6 months after Franck took the job, the level of support tickets exploded and the product quality is deteriorating faster than ever.

Franck rejected everything just to go faster. He was right to emphasize heavily the variable to change. But by doing so, he forgot the other untold values that the team was previously living by. Franck inherited a team of conscientious people. When you stress conscientious people, they become paralyzed.

What could have Franck done better? He should have communicated the tradeoff, not the variable of change. That’s what Zuckerberg did at Facebook. The old mantra was “Move fast and break things“. He stated the focus (speed) and what Facebook was prepared to lose by picking this focus. It was a calculated bet, and everyone was prepared that things could break.

Timing

To conclude: pick the right rejections to build on. It’s like receiving feedback: don’t react right away. Take it, embrace it, analyze it, and then react. You will find hidden gems.