It’s 9PM. You just went through an afternoon of meetings and you just started responding to your emails 1h ago. You still have to finish this new presentation that your sales team is asking for. Zoom fatigue kicks in and you fall asleep on your keyboard.

While asleep the all-mighty God of Business appears in your dreams. As one of the busiest gods around, he directly asks you: “hello fellow servant. You’re faced with a choice: for the upcoming years, you can follow two paths. The first path will give you a very good shot to make $3M in the next 3 years. The second path gives you a 5% chance of having $20M on your bank account in 8 years. Choose wisely”.

What would you pick?

If you’re a first-time entrepreneur without a godly bank account, you’ll most likely rely on rational and mortal down-to-earth statistics and pick the first option. After all, what’s the difference between $3M and $20M ? $3M is already life-changing.

While the answer to the God of Business’ riddle seems obvious, from experience I see many entrepreneurs not picking any path and trying to follow both at the same time. Resulting in a lot of sweat for a poor return.

The problem lies in the fact that most entrepreneurs don’t have a clear strategy about the kind of startup they want to build. Talking to founders I found that growth tactics are well understood, but there are many misconceptions about the arrival line: how startups get acquired. Results: a lot of pain, bad long-term strategies, bad people investment, drastic culture change, a lot of frustration and very poorly optimized cash-return for the founders. Knowing what type of startup you want to build brings peace and efficiency. So it’s a major question to ask yourself, before doing your first customer interview.

The root of the devil lies in the fact that we all read the same passages of the God of Business’ bible. And today, the startup playbook is wrong. What we read are very-risky-big-boom-unicorn building books. Not how to create startups that maximize founders’ returns or impact.

Three kind of startups

Depending on the adventure you want to live, you won’t pick the same vehicle. Who would take a flight for a 10 min travel, and who would go half-around the world by boat? No one. So why do we all structure our startups as rocketships going to Mars?

If we take a look at how startups end up, we can boil down startups to three types:

- The Boat: you’re the captain of your own adventure, exploring the sea at your rhythm and keeping control about where you want to go. You’ll get money by earning an honest salary and an exit strategy is not your priority.

- The Rocketship: go to the moon or go boom. You aim for planet-IPO, with a very high risk, very high reward strategy. Most of your gains will come from a big exit. Rocketships need only one thing: grow higher. And to do so, you’ll need a large crew and a lot of fuel.

- The Dragster: a least commonly used vehicle, dragsters are designed to go as fast as they can in one straight direction, and cross the finish line. Dragster are usually small teams developing a niche product aimed to get acquired by a big company as fast as possible. Low revenues, low dilution, middle risk and reward.

While Rocketship is the most mediated and written about, if you picked the “$3M in a 3 years” path, a dragster is what you need.

Boats and Rocketships: not playing the same game

Boats and rocketships have less things in common than most people think. Sailing and flying are two different sports, and while you need a good crew and tough captains for both, the environment is really different.

Rocketships are driven by the VC-market. It’s go to the Moon or go Boom. For every 10 companies a VC invests in, 6 will die or make no return. 2 or 3 will be close to a breakeven investment. And 1 or 2 compensate for all the other failures. Sometimes those home-run companies pay handsomely : Kleiner Perkins is known for their early investment in Amazon for $8M, bringing a return of ~1 billion dollars. After a home-run like this, you can mess-up investments for dozens of years while still being one of the top funds around. Plus good track records attract good companies, increasing your chance to keep a good track record. Thus, the risk-cursor for VC in how they advise a startup is often more on the risky side

How companies get acquired

Acquiring companies is how big companies get bigger. Selling companies is how founders get rich. With an abysmal percentage of companies that get to IPO, being acquired or dying is the fate of most startups. So while launching a venture, it’s a good idea to understand why and how companies get acquired. If you don’t know the rules of the game, how do you play well?

Big companies mostly buy smaller companies for the following reasons:

- Technology / Product: it’s less expensive to buy a technology than to build it

- Know-how / Acquihire: a strategic transformations needs to happen at BigCorp and they need to bring in people knowing how to do stuff

- Entering a new market: geographic (US → Europe, new country..) or adjacent market. Clients portfolio and cultural understanding are key

- Killing a competitor: see facebook.

You’ve got a lot of other reasons, from financial optimization to brand acquisition, but most startups exit can fall into one of the presented categories.

One of the key points to understand is that for a big company, buying another company is a lot of work. You have lawyers to pay and a lot of due-diligence to do. Then you have to integrate new people into your existing culture. Founders and ex-startups employees’ interests are often misaligned. Technology needs to be integrated in your legacy systems. Sales need to be re-trained, startup’s clients need to be reassured, etc.

Thus: no buying investment if the buying company’s mid-term return is not big enough. Big corp don’t acquire to gain a few millions dollars. They acquire to earn or save dozens of millions.

There are many ways to reduce the cost of acquisition for big corp: incentivising founders to the merger with earnout bonus, adapting salaries for former employees, making light due-diligence when the business is small, etc. But the lesson is: if you want to get acquired, you’ll have to offer a competitive gain/cost balance. Companies below $5M of revenues are rarely acquired for entering a new market or killing a competitor. Rocketships are all about maximizing gain. The goal is to offset the “fixed” costs of an acquisition (lawyers, salaries, ..) by bringing a lot of value. For dragsters it’s another story: they aim to lower the cost side and become “affordable to buy”.

So dragsters tend to be acquired for technology or know-how. Not for revenue, growth or market penetration.

How buyers value your company

So we understand why companies get acquired. But how does the buying side know what price to pay? There are dozens of ways to calculate the valuation of a company using financial metrics. For SaaS, the most common formula is:

Valuation = f(growth, assets)*ARR

The leading metric is the ARR (annual recurring revenue) made by the company. Then it’s discounted or multiplied by two factors: growth and assets.

In growth you’ll of find:

- Year-on-year ARR growth

- EBITDA

- Market benchmark

In assets you’ll find a lot of things from the list “why companies get acquired”:

- Moat

- Technology

- People

- Swag / Brand

- …

Today a good company is usually valued between 3 and 7 times its ARR. It depends on the stage, timing and market mood (a few years ago it was 10-30x ARR). Even what “good” is depends on the timing. So while you’ve got a lot of drivers you can play on, your company valuation doesn’t 100% depend on what you do. As the Serenity prayer said “grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to make VC believe in crypto”.

But all this…… is quants’ theory. The real price of your company is the price a bigger player is willing to pay.

While those formulas anchor a price, give directional trends about your valuation, they don’t take into account the most important thing: what do you bring to the final company that will write the check to buy you?

We all think that the CFO or “VP of M&A” are the ones that make decisions about which companies to buy. Most of the time, it’s not. The real buyers are: CEO, VP Product, CRO and VP Strategy. While the CFO will almost always be involved in the buying process, your real champions are always people on the front-line of the business.

VP Product will buy your company because it takes less time to acquire your technology or people than to develop the feature in-house. It may be because they don’t have the talents, because they’re pressured by a competitor or because it’s just more convenient.

One of the under-valued strategies I know is to build boring companies: developing things that bigger companies need to do but that nobody likes to do. Like maintaining APIs for example. You’re the VP Product of BigCorp and you want to make your app available on every travel platform on earth: what would you do? Spending time to convince your highly efficient developers that supporting 50+ APIs is a great intellectual challenge, and most likely lose 30% of them, or would you buy a company that’s doing just that with a team of passionate engineers already seeing API support as an interesting task? Bonus: they’ve built a 24/7 API support team around the world to be always on watch when Airbnb changes its API without warning. And it costs only a few millions.

No brainer.

Another way to calculate a company value from a CRO perspective: you’re running Sales for a $500M/year company. You know that OfferX would make you win 5% more RFP against your most fierce competitors. Bonus: 40% of your current customer base could use OfferX in addition to their current offer. You make the maths: OfferX would bring $10M in RFP and with pessimistic forecast upsell of OfferX would earn $20M in the first year only. Buying CompanyX that develops OfferX would almost instantly bring you $30M in revenue. And it’s only the first year.

And guess what? CompanyX is only a 10-people company doing $1M in revenue, because they don’t have the proper distribution channel. They’re ok to sell for $10M. So that’s $30M + $1M – $10M – cost_of_merger the first year. The years after, it’s free money.

No brainer again.

So remember: you’ll most likely sell to someone who’s out there on the front, selling and developing their strategic roadmap. 3-7x valuation are theoretical values that we don’t see in the wild. Good valuations come from being identified in a strategic roadmap, creating competition between potential buyers, and most of all a strong, trustful relationship between the buyer and the smaller company.

How does valuation really evolve?

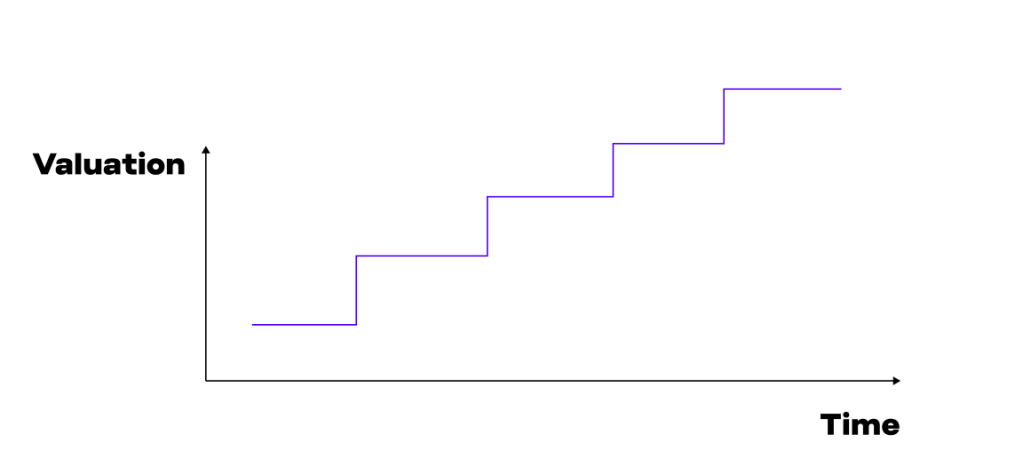

Most people think that companies valuation evolve like this:

It’s almost never the case. First because most successful companies’ growth are quadratic, not exponential.

Second because your valuation is often calculated during VC-rounds. So a more realistic way to see things is per milestones: Series X raised, X million of revenues reached, X users, etc.

That’s great but remember: all these are VC-valuation. They’re driven by VCs that try to predict the final value of your company at the exit or the next round. They are just directions loosely linked to the real check made at the end.

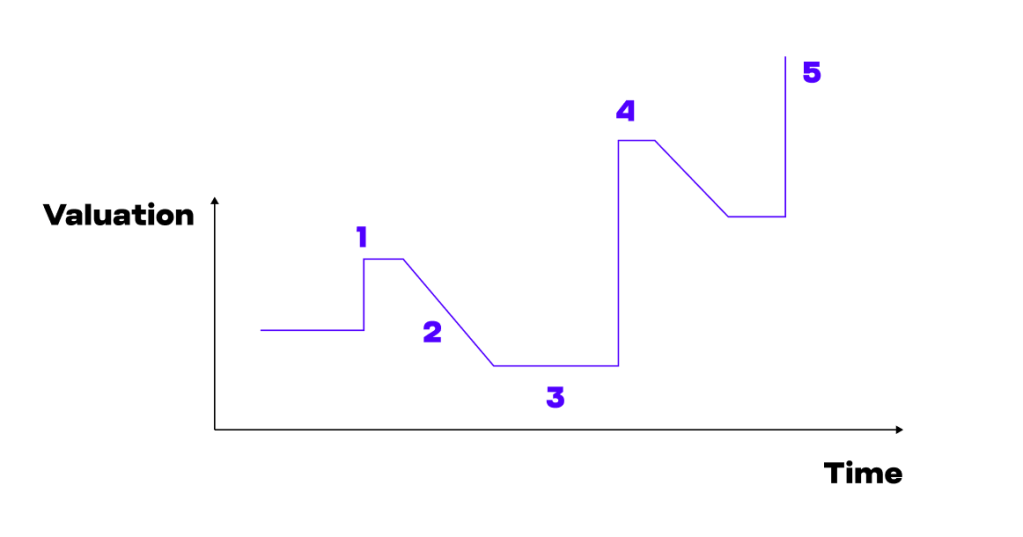

So how does your “buyer-valuation” really evolve? Let’s take the example of a classic company that goes through a few VC-rounds and follow the classic startup playbook.

Your buyer-valuation will go through different steps as you develop your startup. First your valuation will grow quickly as you can be acquired mostly for your technology: you’re super-focused on building your product, and you’re one of the new kids on the market. Acquiring you would be not costly and a bet that your technology would improve BigCorp’s business.

Then your buyer valuation will decrease. In phase 2 you’ve developed most of your product, and your feature growth in logarithmic: 80% of your product real value comes from the first core features you’ve released. You’re not profitable so you had to take some VC-money. Worse: you’re not the only new kid as a few competitors appeared. They’re a bit behind, not as qualitative as you, but they’ve almost developed the 80% of your product value that matters.

Third phase: your buyer-valuation hit rock-bottom. The new kids have copied most of your product value for a fraction of the cost: they just had to copy. So from a technology perspective, they are more valuable than you as they cost less (no need to reimburse the VC that gave you money). You start to have a strong client base but you’re not profitable yet. And you don’t do enough revenues to offset the fixed cost of an acquisition.

Fourth phase: you just reached a significant revenue milestone and you approach profitability. Usually it’s around $5M+ ARR. You’ve demonstrated that there is a market for your product and that you can distribute it. You enter a new world where Private Equity firms and big companies can potentially buy you as you offset the fixed cost of acquisition. You’re profitable or almost, so they can make build-up pretty easily.

Fifth phase: you become a threat for bigger companies, or the symbol of a new market. Buying or killing you becomes a topic in BigCorp board meetings. You’ve not won yet: you just entered the global battlefield. But you’ve got a chance to win a war.

Of course, growth trumps everything. You can skip from phase 1 to 5 if your growth is stellar or your technology is insane. A lot of valuation-plummeting variables can be avoided if you’re fully bootstrapped, etc. But most VC-founded companies I know abide by this trajectory and are always surprised to see their valuation decrease between phase 1 and 3.

Straight line to the exit: how to build good dragsters?

Dragsters are designed for one thing only: optimizing for phase 1. It’s their straight-line race. The goal is to identify a need of the buyer-market, rush towards a technology solution that solves it and then exit as soon as possible. The condition being not spending too much during the process in order to lower the cost of acquisition for the buyer and maximize the financial return of the founders. Dragsters usually aim for a $2-10M exit with 70%+ equity for the founders.

To build a dragster you have to forget a lot of the common-sense written in the unicorn-building playbook. First big change: your real client is the one who will buy your company, not the users of your product. And the implications of this are enormous.

Thus your total addressable market (TAM) doesn’t need to be as huge as the ones for VC-founded startups. Thinking as CRO or VP Product acquirers, you “just” need to represent a 10% capture opportunity of a $100M market to be valued $10M+. So forget the market of “everyone booking an hostel” and welcome the “data-processing feature built internally that makes everyone crazy”.

Get to know your clients: have early conversations with your potential buyers. They’re the ones you want to build trust with. It’s just like Enterprise selling, but it takes a few years to get a multi-million dollar deal. Understand their market trends, how their clients are buying and what’s happening inside of their company. Ask them for advice about what you’re building. Send them monthly newsletters.

In terms of strategy, remember that strategy is making moves to be in the best position to win. Not to check-mate on your next turn. So orient your roadmap and communication towards things that position you well. Look for trends, and invest in Product Marketing. Target the right audience: if your buyers are international, build your SaaS in English first and go worldwide. If you’re targeting a niche, build where the niche is the deepest. Remember that when companies are bought, it can be in exchange of cash or shares. And you usually get an incentive to stay in the merged companies for at least the time of integration. Depending on how you structure your company you’ll be seen as plug-and-play or a long-term integration. It may impact your incentives.

Optimize for what you will sell: your technology. So don’t build a Sales team, chances are that they’ll get valued for $0 if you do less than $5M ARR. Hire developers, product managers and product marketers. Hiring will be one of the deciding factors of your pace during the first years. So have a good balance of specialist and generalist depending on what you build, and hire as few people as possible. Every team member should deliver a big impact on the business. On a rocketship with a hundred of employees or on a slow-moving boat it’s no big deal if you’ve got a few members not 100% performant. But in dragster races you can’t tolerate average members.

Don’t add friction for your users: what you want is to improve your product. If you have to give away a lot of things for free so that you can test and iterate on your product quicker: do it. Don’t put ARR as your main company metric: pick a product related one (# users, performance, etc.).

One of the biggest advantages of dragsters is that the goal is usually very clear and tangible. So it gives you the possibility to align all your stakeholders towards the same thing. Share the value with your employees by giving away stocks, bonus, and push everyone towards the finish line. For your early investors, be clear that your company most likely won’t bring a x1000 upside, but optimizes for a quick and decent return. They’ll be most likely to help you if you set the pace as a sprint instead of a marathon.

Jumping ships: is it too late to change direction?

Sometimes things change and one may want to change the direction of what he’s building. You can turn a boat in a rocketship, but it will need a strong culture change. You can turn a dragster into a rocketship, but you’ll have to structure an acquisition channel and a strong sales team. But you can’t turn a rocketship into something else.

When you’ve burned too much fuel you can’t stop half-way to Mars. At each round you set an expected valuation, and this valuation becomes the floor under which you can’t sell the company and make a good profit. In the shareholder agreement you signed during your fundraising, you’ll most likely have a clause called “liquid preference”. In a nutshell, it means that in case of a sale under your last round’s valuation, investors will get reimbursed first. So selling your company $20M when you raised $21M will bring you almost nothing.

If for any reason you sacrifice your company growth for something else (profitability, new product, …) you’ll still have to reach a higher valuation at the end. And you will most likely be stuck in Phase 3 where buyers can find other players with good enough technology for a lesser cost. VCs can accept that you become profitable for a while to wait for a turnaround of the market, but if they do, it’s that they trust you’ll have the patience and the nerve to wait for a few years with a “reasonable” company.. and start again the race when the market brightens.

Jumping ships is all about opportunity cost. Building one startup is giving up on addressing the million of other opportunities that you see. In the last few years, most startup founders missed bitcoin, AI, and save-the-planet companies because they were busy building their own. Some founders started young, had kids and would now gladly trade their shares for a high-paying company and less mental workload. Some senior founders launched companies and realize that their impact to the world is neutral – or worse noxious. As a CEO, managing people doesn’t make you progress on technologic skills. And leading a startup for a few years gives you skills that are very “bankable” on the market, so you could make a lot of money in the short term. Short-term temptations are always at the corner.

Or it can be the opposite. You can bloom by going faster and deeper in your adventure. A few months ago, the founder of a 15 years old startup, doing 10M€ and having 60 employees told me: “I can’t take it anymore. We’re profitable and all is going well, but… I’ll raise funds. I know that the VC path is intense, current valuations are low, but I want to experience the thrill. I’m so bored that I’m ok to risk it all just to feel alive again”. Today he’s hiring people to turn the mast of his boat into wings for his soon-to-be rocketship.

Finally, some realize that their business outgrows them and they’re not the most relevant captain anymore for what’s coming. David Okuniev – former CEO of Typeform – brought a new CEO and focused on what he loved: innovation. He became Head of R&D at Typeform and launched VideoAsk. Typeform continued to reach for Mars, while David created a small colony on the moon.

Startups give you freedom as much as they enslave you. At the end, it’s always up to you to decide how you want to trade opportunities versus current assets.

What to do now?

The first thing to do is to assess your current venture / idea. Are you targeting a VC-compatible market? Are you building a point-solution that can reasonably expand to a bigger market? Is your business tech or sales driven? Is your business capital-intensive? Start talking to the market and contact potential buyers. Ask for advice and make extra efforts to please your most trusted partners: it’s often them who will buy you or vouch for you.

Then talk to your co-founders and deep dive into what you both want. Sharing this article may be a good way to start the conversation! A lot of companies fail because of co-founders disagreement, so try to align as soon as possible. What do you want collectively and individually? Today and in 5 years? Ask the God of Business’ riddle. You may discover that we don’t all have the same relationship with money. If you’re not aligned, find solutions and make a deal. As startups growth isn’t very predictable, timing may accelerate or slip: so reassess your founder deal regularly. And reassess each time there is a major milestone in your co-founders’ life (kids, wedding, death…).

Launching something is a life-changing experience, and while we must take into account the financial return of the adventure, it’s not the only thing to consider. Startups are one of the best ways to impact the world. Startups are the best environment for hyperlearning. That is why they will break you, reforge you, and make you another person. No matter what you ride.

Discover more from Musing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.